The Central Coast has been experiencing an unprecedented surge in mosquito populations this summer, with some residents describing it as the “worst year ever,” particularly around Tuggerah Lakes and Brisbane Water.

But how do scientists catch, count and analyse the changes in mosquito populations from year to year?

And what are the health risks of contracting a mosquito-borne disease?

According to Dr Cameron Webb, there are hundreds of different species of mosquito in Australia.

Webb, who is a Clinical Lecturer and Principal Hospital Scientist at the University of Sydney, says mosquitos are just as much a part of the Australian environment as any other wildlife.

Each mosquito has a preference for where it lays eggs so changes in the populations of these mosquitoes will be determined by the different ways each habitat fills with water.

At the heart of mosquito surveillance is a humble mosquito trap.

They’re low tech but incredibly effective.

To the passerby, they look like a paint tin and ice cream bucket hanging from a tree, but to a mosquito, they can be irresistible.

The traps use carbon dioxide, often from dry ice or gas cylinders, to attract female mosquitoes seeking a blood meal.

When looking for blood, mosquitoes follow a trail of carbon dioxide, mistaking it for exhalations from animals they feed on.

Unfortunately for them, they’ll end up being sucked into the trap and transported back to a laboratory where they’ll be killed and counted.

The mosquitoes caught provide many insights to guide local health authorities’ responses.

Quite apart from their annoying buzzing and biting, risks associated with mosquito-borne diseases such as Ross River fever are also causing concern.

While nuisance-biting increases, more mosquitoes don’t always mean more disease.

Webb says there is a complex relationship between mosquitoes, wetlands, wildlife and the viral pathogen itself.

Mosquitoes can only contract the virus by biting native wildlife, such as kangaroos and wallabies, and not from emerging from wetlands infected with the virus, making it difficult to predict disease outbreaks.

Fortunately, those trapped mosquitoes can give an early warning of disease risk.

Scientists can test mosquitoes to see if they carry pathogens.

This information is then passed back to local health authorities, which may decide to issue public health warnings or, in some cases, to control mosquitoes.

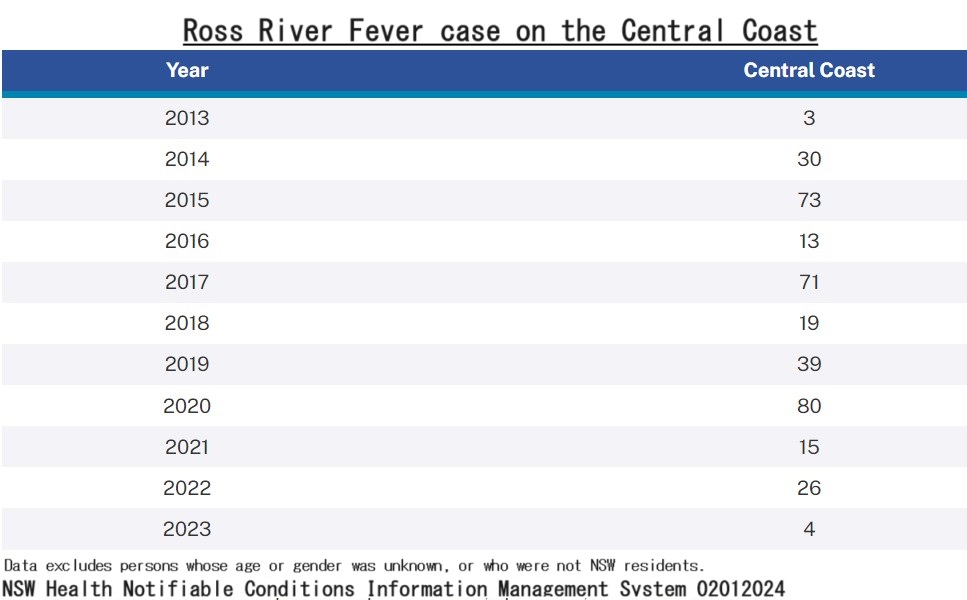

Ross River Fever is a so-called notifiable disease, meaning health practitioners by law must send data about cases to NSW Health.

NSW Health Data on Ross River Virus notifications in the Central Coast local health district over the last 10 years show large swings of infections.

In 2023 only four residents were reported to have had the disease, though in 2020 the picture was different with 80 residents reportedly infected.

It may very well appear to be “the worst mosquito year ever” for many, but fortunately, it seems those numbers have not converted into Ross River Fever as in previous years.