Over 200 people from across the Central Coast attended the Power & Pollution Summit at Lake Macquarie over the weekend of February 8-9. Here are some of the highlights.

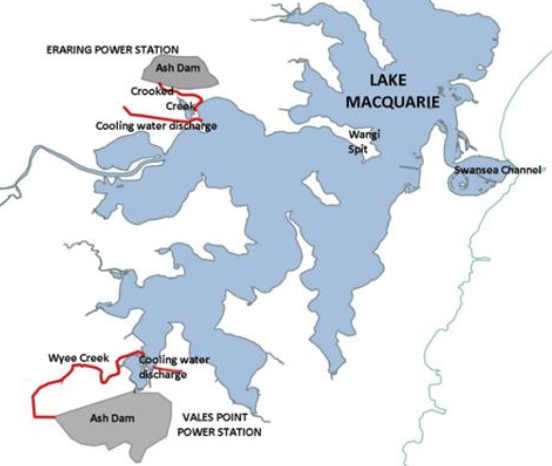

The purpose of the summit was to discuss major pollution challenges for the Central Coast and Lakes regions, with a primary focus on the coal ash dams at Eraring and Vales Point Power Stations.

The event attracted speakers from all over Australia and overseas, including Senior Counsel for Earth Justice in the United States, Lisa Evans.

Evans said the disposal of coal ash was also an immense problem in the USA.

She recounted the collapse of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA) Kingston Coal Ash Dam in December 2008.

The spill was the largest in history with 4.2 million cubic metres of toxic sludge escaping into the waterways, contaminating over 120 hectares of surrounding properties.

Forty clean-up workers died and another 250 remain sick as a result of exposure to the sludge.

The collapse and the ensuing clean-up operation remain the subject of a major lawsuit.

Evans said the collapse of the dam led to stricter regulatory standards on the disposal of coal ash and remediation of ash dams, standards she says that Australia falls well below.

This regulation includes lining of ash dams and comprehensive monitoring or surrounding groundwater for contamination.

Even with tougher standards, she says, environmental disasters may still occur.

In a study of 265 coal-fired power plants in the U.S., including over 4000 well readings, Earth Justice found 91 percent of all sites had ground water toxicity readings above regulatory standards.

A common way to dispose of coal ash is to pump it into disused coal mine voids.

Evans says this is extremely hazardous if the voids are not sealed.

“It is also well documented that building an ash dam over old mine workings is also an extremely risky endeavour, due to the release of leachates” she said.

“Wet storage is the most hazardous because water mobilises the toxic metals within the coal ash.”

Evans lamented the lack of political will to tighten regulations here in Australia.

“Unfortunately, it seems there has to be a major disaster before politicians will look at the regulations.”

Bronya Lipski, a lawyer for Environmental Justice Australia, has been active in the Latrobe Valley of Victoria in recent years, where the majority of Victoria’s electricity is still generated from brown-coal fired power stations.

She says it is important to understand the relationship between remediation of coal mines and ash dams and transitional impacts on local communities.

It is common for many people in local communities to be employed in the sector either directly or indirectly through mining services and other local businesses.

“Communities are however, becoming acutely aware of the risks to their own health and safety, especially when existing laws and regulations offer them little protection,” Lipski said.

She says this was brought into sharp following the 2014 Hazelwood mine fire.

The Hazelwood mine fire burnt for 45 days after a bushfire found its way into the open cut mine, blanketing the townships of Morwell and Moe in toxic smoke and ash.

The local community became outraged as it became evident the mine operators had failed to assess and manage fire risks, to maintain reticulated water pipe systems for fire suppression or to ensure adequate staffing and expertise for fire control despite prevailing weather conditions.

People also became outraged with the initial response from the State Government.

While the fire started on the 9th of February, it was not until the 28th of February that Victorian health authorities acknowledged the risk to the public and recommended evacuation.

Lipski says the Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry highlights the importance of local community action.

“Parliamentary Inquiries are the only way to bring about the regulatory changes needed. It requires people to ask their elected politicians to intervene.”

She says one of the challenges with Vales Point and other NSW coal mines and ash dams are that, as part of their sale to private owners, the government has retained the liability for future remediation, which means ultimately the cost of remediation falls back to the NSW taxpayer.

The ash dams around lake Macquarie may soon be expanded following the NSW Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommendation to approve a proposal from Eraring to expand their ash dam.

Lipski has grave concerns with the proposal.

“The existing ash dam is not lined, is linked to ground and surface water contamination and is causing air pollution – all of which puts the health of the local community at risk.”

An Inquiry by the NSW Upper House into the ash dams has since commenced.

One of the people who will contribute to this Inquiry is Paul Wynn from the Hunter Community Environment Centre.

Wynn is a hydrocologist and author of the “Out of the Ashes” report on pollution caused by coal-fired power stations on Lake Macquarie.

He has been engaged as an Environmental Resources Management (ERM) consultant in site assessments of contamination and, ergo, the future liability of government and taxpayers.

“The ERM reports clarified the state of contamination is very high, well in excess of ANZAC standards.”

He says several studies have also shown the impact on the broader ecosystem, including marine fish and bird life.

“We have found high levels of heavy metals in fish and birds. Feathers examined from the white-faced contained high levels of heavy metals, including Cadmium, Selenium, Arsenic, Zinc and Lead.”

“The ash needs to be removed. It’s not good enough just to be buried under clay, because it just leaches into the lake and surrounding groundwater.”

“Remediation needs to start now, but the EPA licences for Eraring and Vales Point do not require this. They allow them to continue to pollute without any responsibility for the future clean-up.”

“The owners are operating within their licence but not within any acceptable standards. The EPA licence is basically a ‘get of jail free’ card.” Wynn said.

Wynn also says the focus needs to shift to what is feasible in terms of removal.

He advocates for more research and development of commercial opportunities for reuse, including lightweight aggregates (building concrete) and other cements.

“The higher the carbon content, the more the ash can be used for high-grade construction.”

Another perspective to the issue of pollution and mining-related remediation came from Lachlan Rule from Beyond Zero Emissions (BZE).

Rule has worked closely with the Western Australian community of Collie, a coal mining area two hours south of Perth.

Rule says that 1,250 jobs were at risk from the closure of the coal mines but that their study found that a co-ordinated, government-backed initiative to create a renewables industry in Collie, including solar PV cell recycling facilities, grid scale storage using pump hydro technologies and the development of engineering by-products from coal ash, had the potential to collectively create over 1,750 new jobs.

“People were not keen to have that conversation however,” Rule said. “It’s something that would require government policy support.”

Professor John Wiseman from the University of Melbourne and ANU agreed on the critical role of government going forward.

He believes that the closure of coal-fired power stations in Australia will likely happen faster than is currently expected, beginning with the closure of Liddell in the Hunter Valley in 2022-23.

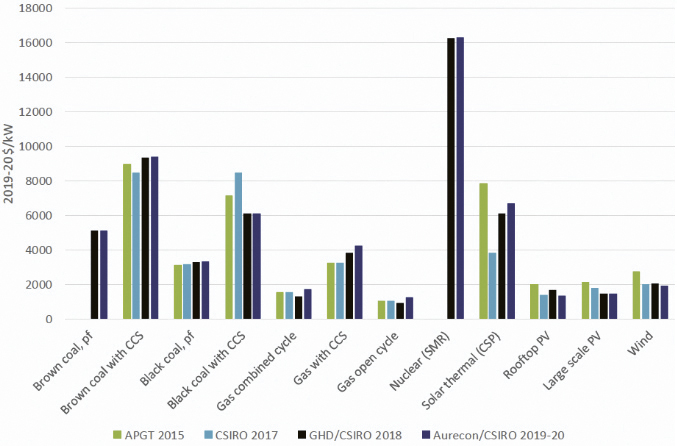

He said lower demand, greater use of renewables, increasing operating and capital maintenance costs of coal-fired station were all working to make coal-fired power uneconomic.

“The technologies already exist to support a large-scale transition to renewables at a lower cost, including lower capital costs,” Wiseman said in his presentation. “We just need the right policies now to promote green industries.”

Ross Barry